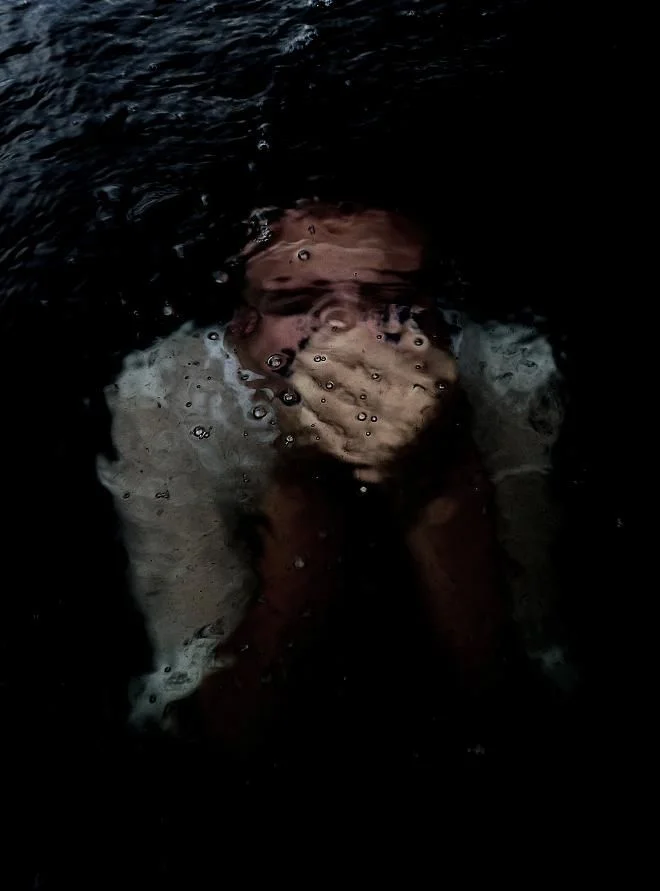

I can’t remember the first time I disappeared.

It’s hard to stand up and face life. It’s all too easy to just go away.

It’s simple to feel like you’re one and the same as everyone else when you go to an Orthodox Jewish girls’ school. There, everyone dresses the same - skirts hitting four inches below the knees, loose shirts covering the elbows and collarbones, and hair tied neatly back in a ponytail. It’s a simple enough act to fade when everyone is the same. But I didn’t feel like everyone else. I never could fade properly. I was the girl who wore too much black eyeliner. The one who knew all the laws she was supposed to, but had a hard time implementing them. The person caught staring too long at the other girls in the class. I was the bright red in a world where we all wore black.

I knew there was something wrong with me from the moment memories began to stick in my head. I was tortured by my mind, and I was desperate to be free. The first time I attempted suicide was when I was seven, and that started a pattern. I realized that no one would see that there was something wrong unless it was very visible. I needed help; I knew that much, but I didn’t understand that had I told someone what was going on inside my head, I would have received assistance. I thought that only people with visible illnesses would receive the help I so desperately needed. I began to wish that I would wake up one day and not have my sense of vision anymore, or that I would be paralyzed from the waist down. It didn’t matter much to me that I wouldn’t be able to ride my bike anymore, or that I wouldn’t be able to look out the window of our car during long road trips. If it meant me and my pain would be seen, I would have taken it.

After a particularly nasty suicide attempt, I was finally hospitalized. Since at the time I had no health insurance, I was sent to a state hospital where I was sexually assaulted for the fourth time. I wanted to die there, but I had no way out. I learned how to lie, how to say I was okay, when really, nothing was.

Learning that there was nothing ‘wrong’ with me took years. And along with that, I learned many other things, vital life lessons that I should have been taught as a child. I learned how to say I wasn’t okay. I learned how to fight back. I learned how to be angry. I learned how to be me, an agender asexual bisexual person with Bipolar II and an eating disorder. I learned how to scream. I learned how to love.

I wish I could say it’s over, for me. I wish I could say that I don’t suffer anymore. Something else I learned is that freedom takes time. Freedom sometimes takes hundreds of years. I wonder, though, if it’s worth waiting hundreds of years for something we can generate immediately. I wonder if we can pool our suffering, if we can talk about it, then maybe we can make our own exoduses happen right here, right now.

I am not here to disappear.

I am here to talk about it.

You can read follow Shay on Twitter at @gothicfishie